Arabian Type, Part Two

by Cindy Reich

In this second installment of “Arabian Type,” we look at the Arabian’s short back, nearly-level croup and high tail carriage, all hallmarks of the five characteristics of type that define the breed. We will check in with the standard of excellence from several countries and associations, to determine what the template should be for evaluating these characteristics. Then we will delve into how these characteristics evolved.

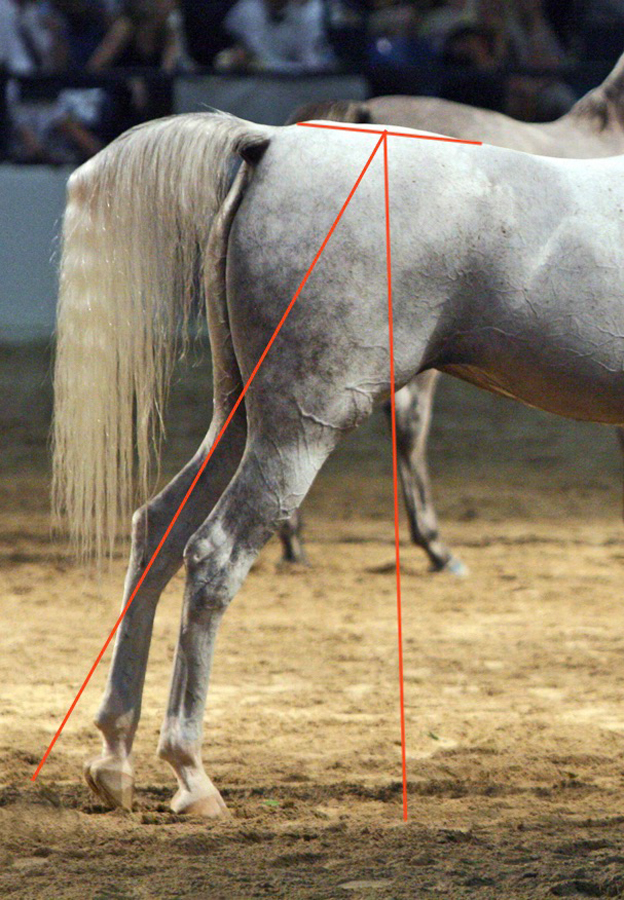

It would be hard to find a better depiction of the Arabian’s ideal tail carriage and level croup than this photograph of *El Nabila B (Kubinec x 218 Elf Layla Walayla B).

It would be hard to find a better depiction of the Arabian’s ideal tail carriage and level croup than this photograph of *El Nabila B (Kubinec x 218 Elf Layla Walayla B).

The Pyramid Society has this to say about the back, croup, and tail carriage of the Arabian:

“Shortness of back with good muscling is a hallmark of the Arabian breed. Mares may have slightly longer backs than stallions, but the loin should be broad and strong, providing strength and balance.

The more nearly horizontal croup is preferred over that which is sloped, but some roundness allows more athletic movement. Likewise, an upward tilting croup is not desirable.

“The croup should be well muscled and full, and the point of the croup should not be higher than the muscles on either side of it. The croup should be long and comparatively level, with the tail flowing naturally into a high, elegant carriage. The tail setting, at rest, should be level with the back and not with the point of the croup. The croup becomes more horizontal in motion, raising the tail setting. The buttock, set high, projects back well past the point where the tail meets the body.

“The Egyptian Arabian horse is noted for a distinctly high, proud tail carriage. This is natural to the horse and evident even when still but alert and focused. Upon movement the tail iselevated in an arch, and upon excitement or animation, is carried gaily - often flagged in the air. The set of the tail should be high, and the tail should be carried straight when viewed from behind.”

“The buttocks high and the tail set on at a high point. The head and tail should balance his outline when in motion. The tail set on high, arched and carried gaily in the air at the first motion of the horse. (W.R. Brown).”

From the Australia Standard of Excellence for the Purebred Arabian Horse:

“The croup should be long from point of hip to point of buttock. It should also be long and comparatively horizontal from point of croup to butt of tail. At rest, the tail setting should be level with the back and not with the point of the croup. In motion the croup becomes more horizontal, raising the tail setting. The buttock is set high and projects back well past the point where the tail meets the body.

“Note that there has to be a visible rise from the back, over the loins, to the point of the croup, followed by a lowering of the croup to the butt of the tail. The butt of the tail is seen to be set into the horse level with the back when viewed from the side.

Viewed from behind, the croup should appear wide and strongly muscled and the point of the croup should not project above the muscles on either side of it.”

Interestingly, there is nothing in the Standard of Excellence addressing the horse’s back. As to tail carriage, this is the template: “When the horse moves, the tail is elevated to be carried proudly in a high, pronounced arch.”

The Arabian Horse Association of America Standard of Excellence is a bit more succinct in their description: Short back, croup comparatively horizontal. Tail — natural high tail carriage. Viewed from rear, tail should be carried straight.

The ECAHO Judge’s Training Manual says this about the croup: “The point of croup is the highest point of the quarters, ideally the same height or slightly lower than the withers. The croup should be reasonably long, and level and it extends back to the root of the tail which should be carried as a natural extension of this line.

“Tail set and carriage is an important and distinguishing feature of ‘Type.’ The tail arches away from the quarters and is carried like a banner when the horse moves. It may plume right over the back when the horse is excited. A slight sideways carriage of the tail is acceptable.

“The Arabian should have a relatively level, strong back and there must be room for a saddle. It should be well muscled on either side of the spine running into a short, broad close-coupled loin area. The Arabian can have 17 pairs of ribs rather than the more usual 18 or 19, five lumbar vertebrae instead of six, and 16 instead of 18 tail vertebrae.”

How did these characteristics come to define “Type” in the modern-day Arabian horse?

I remember back in the day, when the Arabian was supposed to carry one less vertebra in the back, and one defining characteristic of the Arabian horse was its extremely short back. In “The Authentic Arabian Horse,” Lady Wentworth contended that the purest Arabians had one less lumbar vertebrae and one less rib. And that “cold” blooded horses had 19 ribs and six lumbar vertebrae, better-bred horses had six lumbar vertebrae and 18 or 19 ribs and Thoroughbreds had 18 ribs and six lumbar vertebrae. She goes on to list data from purebred Arabians as follows:

| Ribs | Lumbar Veterbrae | ||

| 50 | Specimens | 17 | 5 |

| 9 | Specimens | 17 | 6 |

| 4 | Specimens | 18 | 5 |

| 1 | Specimens | 18 | 6 |

| 3 | Syrian Arabs | 17 | 6 |

Interestingly, she gives data on some Thoroughbreds from the time and of 12 listed, half had 5 lumbar vertebrae and half had six lumbar vertebrae. Obviously, the influence of the Arabian in the foundation of the Thoroughbred may have had an effect. She also included data from other equine species such as Barbs, Zebra, Donkey and Mongolian. The Donkey and the Mongolian had five lumbar vertebrae and the rest, six.

She goes on to list more data from horses of her own breeding stock, where the majority had five lumbar vertebrae. Gladys Brown Edwards lists data in her “Anatomy and Conformation of the Horse” whereby of 10 Arabian skeletons measured, seven had six lumbar vertebrae and three had five lumbar vertebrae. What does that mean for us? Basically, that Arabians can have either five or six lumbar vertebrae.

The number of lumbar vertebrae is more indicative of the shortness of the coupling than of the back itself. The “coupling” is the distance measured from the last rib to the point of the hip. A short coupling would be the distance of three fingers side to side. The longer the coupling, the longer the back appears. Other things that affect the visual length of the back are the shoulder, withers, and ribs. For example, a horse with a straight shoulder and low withers can have the appearance of a long back. A horse with a ribcage that points backwards rather than straight down will appear to have a shorter back. A horse with a well sloped shoulder, prominent withers and short coupling will appear to have a short back.

Short back – Why a short back? The intended function of the Arabian horse is to carry a rider (or goods) over long distances. A short back is a better weight carrying structure. A short back also makes for a more balanced way of moving as it ensures that the center of gravity is directly behind the withers.

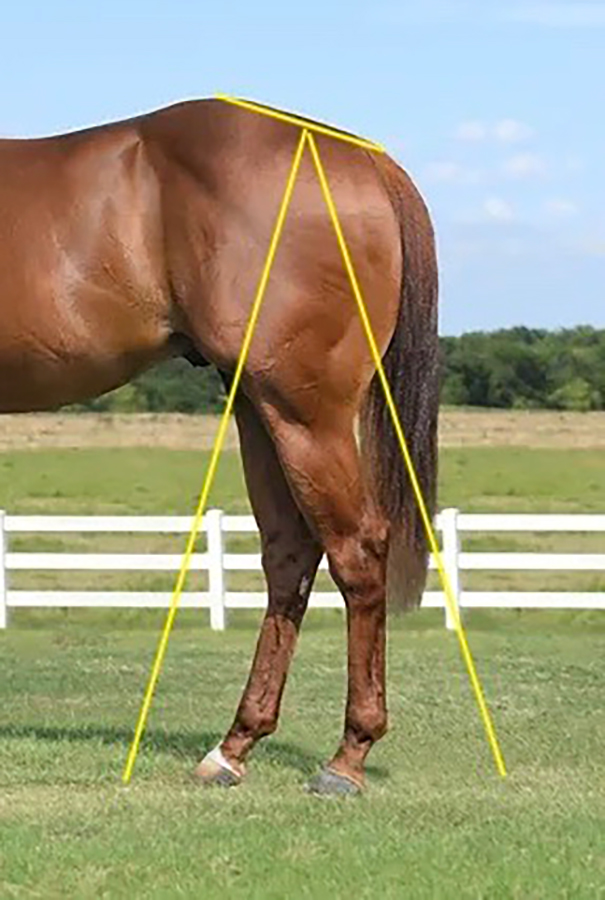

Comparatively horizontal croup – The advantage of a long, relatively horizontal croup is in biomechanics. The longer and more level (not going uphill) the croup, the more efficient and ground covering is the path of the hind leg in motion. It covers more ground in each swing of the leg and is closer to the ground. Like a pendulum, this arc of the hind leg can be sustained for a long time without fatigue. The horses that evolved in the desert had to cover a lot of ground efficiently, and thus were more useful to the Bedouin, whether as transportation or in battle. This is why the Arabian still reigns supreme against all breeds as an endurance horse. Its conformation evolved to produce a horse that was a more efficient, ground-covering mover.

High tail carriage – While everyone admires a horse that carries its tail proudly arched, the Arabian must have this attribute. It too, is a result of the desert environment in which the Arabian horse evolved. There are two major blood vessels under the tail. In the hot air of the desert, raising the tail acts as an air conditioner —air flowing under the hairless underside of the tail cools the blood supply going to and from the heart.

These characteristics of type were forged by the desert environment and were vital for the survival of the Arabian horse. Man has since selected and refined these characteristics for his own purposes, but bear in mind that the Arabian’s defining traits reflect his unique heritage.