Arabian Type - The Head

By Cindy Reich

This is the final chapter of the series examining the five traits that constitute Arabian type.

I left the head for last because it seems that too much attention is focused on the head, which is only one of the five traits of type. Yes, it is clearly the most easily recognizable trait, however it is part of the whole, not the only defining characteristic.

Performance horses show plenty of desirable Arabian type in the head while retaining their function.

Performance horses show plenty of desirable Arabian type in the head while retaining their function.

Bette Finke recently wrote a great article for The Swift Runner about the Arabian head, and I encourage students of conformation to read and absorb what she had to say. She brought up the interesting topic of the position of the nasal bone influencing the degree of “dish” when the head is viewed in profile. In this article, we will break down the main parts of the head to reach the foundation of how the head characteristics came to be quintessentially “Arabian”.

The Arabian horse originated in a tough and challenging environment as a desert animal. It was a prey species for the desert lion, leopard, and cheetah. There is very little cover in the desert, so the vistas are vast, and animals that could easily see any danger had a higher chance at survival. Horses have a wide range of vision, as their eyes are set on the edges of a wide forehead. This prominent placement is essential to survival as a prey species, as it covers the greatest range of vision. With a straight or slightly concave profile, the Arabian horse’s eyes had an unobstructed view. The larger and more prominent the eye, the greater the field of vision.

This wide, unobstructed field of vision not only allowed the Arabian horse to see danger to itself more easily, but it also made it a more efficient war horse. The ability to see an enemy well in advance of contact for the rider would have meant the difference between life and death for Bedouin tribesmen.

The thin skin and prominent veins on the Arabian’s face aid in cooling the blood at the surface of the skin—not only because of the desert environment in general, but more importantly, when the horse is running. Under exertion, whether fleeing from a lion or chasing an enemy with a rider, the blood vessels on the face would help cool the blood at the surface as air passed over the horse’s face. This same process also explains why the Arabian has a high tail carriage. Major blood vessels running underneath the base of the tail, are cooled when the tail is carried high. It is important to understand these traits are products of the Arabian horse’s evolution, not a whim based on what humans thought were attractive.

Which brings us to the head as a whole. In every standard of excellence, the head is described in profile as having anything from a straight to a slightly concave profile to the face. I have yet to find a standard that mandates an extreme dish to the face with an abnormally small muzzle. Yes, the Arabian should have a smaller muzzle when compared to its jowl and the standard does say the head should appear triangular when viewed from the profile. However, the extremes being rewarded in the show arena today are not what the standards require.

In the past ten years, the emphasis being placed on the head alone—regardless of the rest of the horse has changed the breeding and show industry. What is important to understand is that if something is extreme, it is not necessarily better. Particularly if it interferes with function. Then it is simply extreme, but non-functional is never better. From an evolutionary standpoint, if one looks at early photos of Arabian horses, there are no “dolphin heads” to be found. From an evolutionary standpoint, the “dolphin head” would not have been an asset in any way. The extreme bulge between the eyes (slip jibbah) reduced the horse’s ability to have a wide, unobstructed view.

A severely dished face reduces the space in the skull. This can cause crowding of the teeth to the extent that the horse cannot eat or chew properly. All the dimensions of the face are distorted, which often results in nostrils that are vertical and not the large, round nostrils that are asked for in the standard. Under exertion in the hot desert, the larger the nostrils, the more air that can be taken in. This air needs to be cooled as it passes through the head (skin, prominent blood vessels). Horses are obligate nose breathers—they cannot switch to breathing through their mouth when they cannot get enough oxygen. Therefore, anything that increases resistance or reduced air flow lowers that horse’s ability to function properly, especially under exertion.

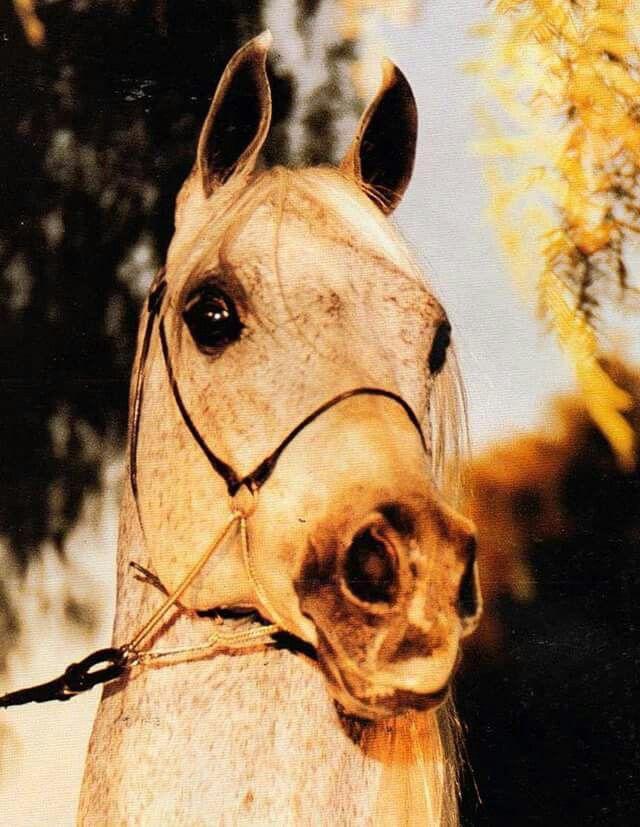

A beautiful example of type and femininity that is also functional, Negma al Shaqab

A beautiful example of type and femininity that is also functional, Negma al Shaqab

Let’s go back to the function of the horse—it is to carry something or pull something. From the first days of domestication, the horse has been a service animal. Clearly, a horse with extreme features to the head that interfered with function would not survive as a prey animal and would not be a functional animal for its intended purpose. However, in modern times, horses are not evading lions in the desert. Their food is prepared and brought to them to eat. If they have trouble eating or chewing, accommodations are made. The modern halter horse does not exert itself during the course of a show to the degree that it impairs their function. Therefore, all the extreme features that are being rewarded and driving even more extreme forms, are never tested as a functional animal. To test that theory, look at the head of the horses in performance classes. You will not find the exaggerated, extreme head because it is not synonymous with function. Yet most performance horses have beautiful heads—just not extreme heads.

Understanding how the Arabian horse’s evolution and function shaped those characteristics that define it should make it easier to recognize and reward those that fulfill the standard of excellence. Avoiding and not rewarding non-functional extremes will ensure that the breed characteristics that define the Arabian are based on function and not man’s interpretation of what the Arabian horse should look like.