It’s All in the Head (- or is it?)

By Betty Finke

Ask anyone why they fell in love with Arabian horses, and chances are they’ll tell you it’s because of their beauty. Even over 200 years ago, when the first Arabians were imported to Europe from the Desert, people raved about their beauty and artists immortalized it in their paintings and sculptures. Though the horses were imported chiefly to add speed and stamina as well as refinement to the local breeds, their beauty was always an essential part of their attraction.

Looking at photos of those foundation horses now, we may well wonder what their contemporaries saw in them. To our eyes, accustomed to the ultra-refined show horses that populate print and social media today, they look plain and unremarkable. But beauty, as they say, lies in the eye of the beholder. To get the full picture, we need context. Part of that context is that in the past, horses in general were much heavier and coarser than they are today. By comparison, those early Arabians appeared exciting and exotic, even if they seem plain to us now.

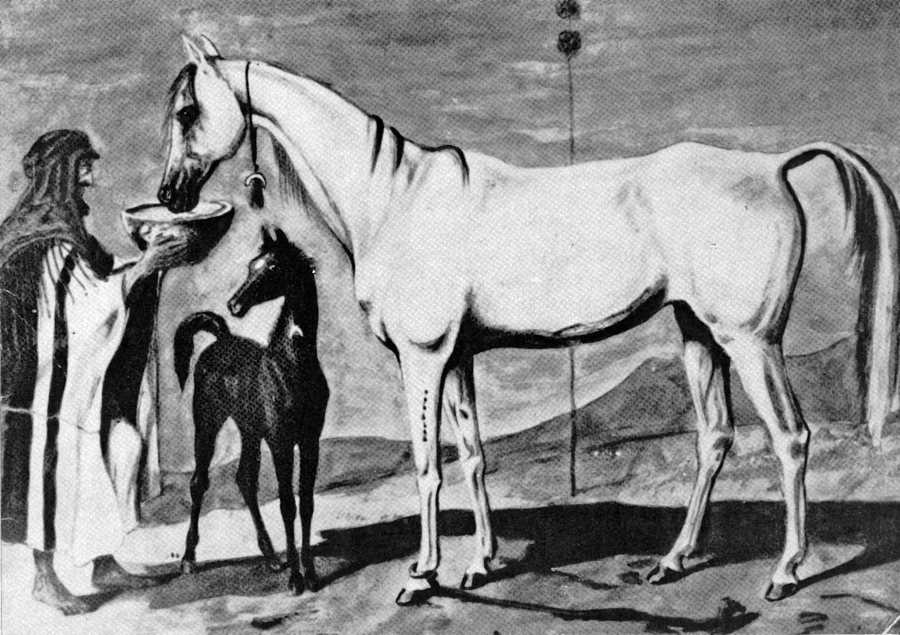

We must also remember that photography was very different in those days. Today, photos of Arabian horses are carefully staged works of art. They may even involve some discrete manipulation by way of modern software technology, because they are not intended to show facts, but to create an image. Equine photography in the 19th and well into the 20th century was documentary. It showed the whole package, making no attempts to disguise faults and/or enhance type. Unless the photographer was Lady Wentworth, that is, who notoriously retouched her own photos, lifting tails, tucking up sagging mare’s bellies, and painting over entire heads to shrink down the muzzle and enlarge the eyes. Fortunately, those “enhancements” are glaringly obvious and unlikely to fool anyone.

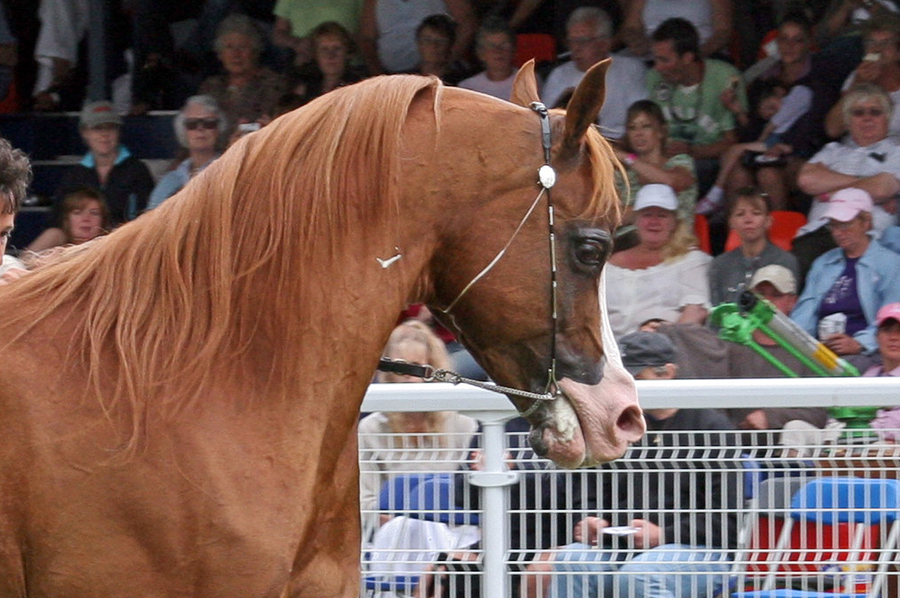

The photos accompanying this article have been selected to show the wide variety of Arabian heads... What they have in common is that these are all typey, beautiful Arabian heads, with or without jibbah or any kind of dish at all.

But, obvious as they may be, they foreshadow a problem we have today. Lady Wentworth was striving towards an ideal. Like her mother, Lady Anne Blunt, she was a talented painter, and her art reflects those ideals. And when her photographs of her own horses didn’t conform to that ideal, she simply painted them into the proper shape, especially their heads.

But what, exactly, is the “proper” shape? No one can deny that the Arabian head is its most distinctive feature, and a vital factor in defining both the breed’s beauty and its overall type. It is not the only one, though. Tail carriage is another, and in fact a high tail carriage in any horse is a far more reliable indicator of Arabian blood than the head. For most people, type starts (and all too often ends) with the head. When we look at paintings by 19th century artists who portrayed early Arabians, whether it’s Emil Volkers or Albrecht Adam in Germany or Juliusz Kossak in Poland, we invariably see ultra-refined heads with huge, bulging black eyes, wide-open nostrils, and tapering muzzles. These have always been hallmarks of the breed and are described in great detail by early European travelers as well as by the Bedouins themselves. If a horse doesn’t have these features, it is not a typical Arabian. If contemporary photographs show those same horses as less than ideal, you have to remember that photos only capture one moment, frozen in time. We also have to remember that the same horse, when animated and in motion, will have looked very different. Arabians can look quite unremarkable and even boring when at rest, only to transform completely when bursting into movement. This phenomenon was already noted by Carl Raswan when he was living with the Bedouins in the Desert, and this may well be why modern showing insists on posing them all tense and hyped-up. It is an attempt to replicate in repose what, normally, you only see in motion.

But one thing you will rarely find in those early paintings (never mind photos) is the one thing people seem to associate most with Arabian heads today: the so-called “dish,” that distinctive concave profile between the eyes and the nostrils. If you look closely, you can detect a slight concave line in some images, but many heads are perfectly straight. Very refined, with almost freakishly big eyes and wide nostrils, but straight.

The same is true of many historic horses that are still celebrated today for their beauty. Great mares like Egypt’s Moniet El Nefous, Poland’s Bandola, Algeria, or Pilarka, or the legendary Spanish-bred Estopa, did not have much in the way of a dish. At most, they had the classic, slightly concave line of profile that appears in those 19th century paintings and which is, in fact, described in most breed standards around the world.

…a high tail carriage in any horse is a far more reliable indicator of Arabian blood than the head.

The German registry, for example, specifies that the profile should be “straight or slightly concave,” as does the Arabian Registry of South Africa. According to the Australian standards, “the majority of Arabians exhibit a dish or depression in the profile of the face. The dish is situated about halfway between the poll and the muzzle, and varies considerably from almost imperceptible to quite pronounced.” In the USA, the AHRA standard says “profile of head straight or preferably slightly concave below the eyes; small muzzle, large nostrils, extended when in action; large, round, expressive, dark eyes set well apart.” Note that in all these cases, a straight profile is perfectly acceptable in combination with the other required characteristics, i.e. large eyes, small ears, wide nostrils, and overall refinement. Not to forget that the profile is not the only outstanding feature of the Arabian head; another is a broad forehead with eyes set wide apart, as seen from the front.

All these standards allow for a considerable variety of different head shapes, all within the standard and conforming to the Arabian horse of the Desert. But on the website of the Arabian Horse Association (AHA), we find a very different description in the context of educating young people about Arabian horses. Rather than referring to the AHRA standards, this description states that the Arabian head should have “large and wide-set eyes, bulging forehead, dished face, flaring nostrils, small and refined muzzle.”

Whatever happened to “profile of head straight or preferably slightly concave?” The standard, which normally allows for some variety of head shapes, has suddenly been narrowed down to exclusively dished faces with bulging foreheads.

And why does everyone now follow suit, ignoring the original standard? How did this happen? And why do all other countries now follow suit, ignoring their own standards and concentrating almost exclusively on those bulging foreheads and dished faces? Not only that, but they seem to be following an unwritten instruction that states “the deeper the dish, the better the type” to the point where some horses begin to look like caricatures.

Don’t get me wrong: there is nothing at all wrong with the dish as such. It has always been around, and has always been a notable feature of the Arabian horse. The Bedouins had a term for it, afnas. The word “dish” is actually misleading, because it implies a depression or dent in the head. While some horses give that appearance today, this is not what it originally was, at all. In order to put things into perspective, we have to understand what exactly the “dish” is, and also, that there is more than one type of dish.

Some horses may have the capacity to extend their nostrils so widely that the entire nasal area tilts upwards, creating the appearance of a dish.

The original, classic dish, as it were - i.e. the one most often seen in 19th century images – is a gentle concave line of the profile beginning below the eyes and caused by a prominent forehead. This prominent forehead, which the Bedouins called jibbah, can vary from just slightly raised to a prominent bulge. Below this bulge, the profile may either continue in a straight line down to the nostrils, or appear distinctly concave because the nasal bone rises up again towards the muzzle. These two features, the jibbah and the raised nasal bone, are responsible for the more extreme types of dished profile and show that the name “dish” is in fact misleading. It is not a depression in the profile, but rather the result of raised bone. This is significant in that it disproves the often heard argument of the anti-dish crowd which, in reaction to the extremes we see today, have become very vocal lately. They like to claim that the dish (never mind how deep) hinders breathing. It does not. The classic dish caused by the jibbah and the raised nasal bone does not affect the flow of air. The Bedouins relied on their horses for speed and agility, using them for raids. They also liked this type of head, and they certainly wouldn’t have if it impaired a horse’s performance. We are not talking about modern excesses here, but of the original, classic Arabian.

There is also another, very different type of dish, which is really an illusion. These horses have almost straight profiles, with only the very slightest inward curve, and neither a prominent forehead nor a raised nasal bone. The forehead even may be completely flat. But such horses may have the capacity to extend their nostrils so widely that the entire nasal area tilts upwards, creating the appearance of a dish. This is a phenomenon found in many of the straight Egyptians of Dr. Nagel’s breeding. These horses are celebrated for their extreme type, but don’t really have much of a dish. They do have enormous eyes and nostrils, and when they really blow out those nostrils, their heads look spectacular. This is also true of some historic horses who were known for their “extreme” heads at the time, but were nothing like today’s horses. One of them was the early Crabbet sire Irex, who was famous for his head, yet his photos show a perfectly straight profile. This puzzled me for years, until I observed this flared nostril effect in one of his descendants, who resembled him a lot. There is also a third type of head that may appear dished, but really isn’t. Just as there are horses with a large jibbah and a straight line of profile below, there are some with a flat forehead, but a raised nasal bone.

All these types of heads, though distinct from each other, are classic Arabian heads, but only two of them have an actual “dish:” the slightly concave profile shown in 19th century paintings, and the more pronounced version caused by a more prominent jibbah and raised nasal bone. For some inexplicable reason, there seems to be a consensus in show circles that the latter should be the standard not only to strive for, but to take to the extreme; notwithstanding the fact that the sires who were instrumental in creating the modern show Arabian didn’t have this type of head at all. Neither WH Justice nor Marwan Al Shaqab, whom no one would deny being very typey individuals, have an exaggerated dish. Both have perfect, classic Arabian heads: Marwan Al Shaqab with only a slight jibbah and moderate dish, while WH Justice is a classic example of a head with no jibbah, just the slightly concave line of profile. Both have the wide, expandable nostrils which, when fully open, cause the profile to rise over the nose and enforce the appearance of a dish. These are classic Arabian heads of the kind shown in 19th century paintings. Why is this suddenly not good enough anymore?

Exaggerated dishes have always existed, but they used to be the exception, not as prevalent as they are today. When they did appear, they were definitely eye-catchers, causing varied reactions. I remember when one of the most decorated European show mares of all time, Essteema, made her first appearance, someone asked me: “Is that head a fluke, or is it genetic?” She sported a pronounced jibbah in combination with a very refined face and teacup muzzle, rarely seen in those days. No raised nasal bone, however, so you could argue if it even qualified as a “dish,” but it was certainly distinctive. Having known her dam line for several generations, I could confidently reply: “It’s genetic.” That pronounced jibbah had been a consistent trait in her dam line for several generations; they had all been winners and all noted for their extreme heads. Essteema became the first Triple Crown-winning filly in history. While her extraordinary head may have been a factor, it wasn’t the only one; like her tail female ancestors, she was an overall excellent individual and went on to become a broodmare of some significance. But it’s the head everyone remembers.

… the extreme has now become the ideal, and that is worrying. The implication now is that if it’s not extreme, it’s not good enough.

Around the same time, in the late 1990s, another spectacular show mare made an appearance: SHF Pearlie Mae. Bred in the U.S. and owned by the late Shirley Watts in Britain, this mare had a dish that was exaggerated to a freakish degree even by today’s standards. It was certainly divisive. People either swooned over her, or were appalled. The judges all put her first, because – much like Essteema – she was not just a pretty face, but an altogether excellent individual. But, unlike Essteema, she was a fluke. Neither her parents nor her full siblings had heads like that, and she never passed it on. On the contrary: when bred to the ultra-typey Simeon Sadik, a stallion known for his own (at the time) extreme head, she produced a perfectly fine, but completely straight-faced colt. This might tell you something about nature correcting mistakes.

There was another mare of this kind around at the time in the U.S., Muscamoura. I never saw her in the flesh, but photos and videos show a head even more freakishly exaggerated than Pearlie Mae’s. She was straight Russian, and while Russian lines (more specifically, Aswan) were certainly responsible for the prominent jibbahs as seen in Essteema, nothing in her breeding could explain a head like hers. As far as I know, she never passed it on, either. Again, it was clearly a fluke and may even have been caused by some outside influence before birth – something pressing against the head of the foetus – rather than genes. I saw a foal once that had a crooked muzzle because of this, so it can happen.

Whether it was flukes like that, or the proliferation of the blood of Aswan, who was clearly responsible for the bulging foreheads, people seem to have become obsessed with the dish, trying to take it to the extreme on the one hand and completely disparaging it on the other. Every breeder strives towards an ideal, which is only natural. But it seems for many, the extreme has now become the ideal, and that is worrying. The implication now is that if it’s not extreme, it’s not good enough.

Let me give you an example: a few years ago, a friend of mine bought a mare in foal to a show stallion with an extreme head. The mare produced the most gorgeous filly, with a lovely head and the biggest, darkest eyes. Yet when a show trainer came to look at this filly, he told my friend she was not typey enough. And that neatly sums up the problem.

Part of the problem is, of course, that many breeders don’t even realize there is a problem, because the judges keep awarding the highest marks to the most extreme heads. It’s a vicious circle, and if you want to know where this can end, look at what has happened to some dog breeds. Whether it’s the sloping topline in German Shepherds or the flat nose in French Bulldogs, some have been bred so single-mindedly towards one defining feature that they end up having to be put down because they either can’t walk or can’t breathe. These breeds produce dogs that are unfit to live, because they concentrated on a single feature and took it to the extreme.

We would do well to learn from this. The Arabian may be known for its “teacup muzzle,” but some muzzles are becoming so small they no longer have room for the teeth. And while a proper dish does not affect breathing, we are now starting to see heads that are actually bent, the lower half no longer aligned with the upper, but at an angle which, of course, enforces the dished appearance. If this continues, where will it end?

The photos accompanying this article have been selected to show the wide variety of Arabian heads. Some are historic horses, some are modern ones; some are famous, some are obscure; some are show horses, some are not. What they have in common is that these are all typey, beautiful Arabian heads, with or without jibbah or any kind of dish at all. A few might be called “extreme,” for one reason or another. Extremes may occur in any breed, but they should remain the exception. They should never become the standard.

Juliusz Kossak’s iconic portrait of the desertbred foundation mare Sahara, early 19th century. Clearly an accurate depiction (including a less than ideal topline), and showing an almost straight profile.

Juliusz Kossak’s iconic portrait of the desertbred foundation mare Sahara, early 19th century. Clearly an accurate depiction (including a less than ideal topline), and showing an almost straight profile.

Detail of the portrait of a mare from the stud of Abbas Pasha I of Egypt, showing a very refined head with huge eyes and a perfectly straight profile.

Detail of the portrait of a mare from the stud of Abbas Pasha I of Egypt, showing a very refined head with huge eyes and a perfectly straight profile.

Detail of a 19th century painting showing a stallion at the Weil stud of King Wilhelm I of Württemberg, with huge eyes and nostrils and a slightly concave profile.

Detail of a 19th century painting showing a stallion at the Weil stud of King Wilhelm I of Württemberg, with huge eyes and nostrils and a slightly concave profile.

Photo of the early Crabbet sire Naufal (Sotamm x Narghileh), bred by the Blunts. His profile is straight, but the eye big and the overall texture very refined.

Photo of the early Crabbet sire Naufal (Sotamm x Narghileh), bred by the Blunts. His profile is straight, but the eye big and the overall texture very refined.

A modern desertbred mare from Bahrain: flat forehead, slightly raised nasal bone, big nostrils.

A modern desertbred mare from Bahrain: flat forehead, slightly raised nasal bone, big nostrils.

Li’ba (Hlayyil Ramadan x Lamees), a mare bred by the Royal Jordanian Stud, with a pronounced jibbah, but no actual dish.

Li’ba (Hlayyil Ramadan x Lamees), a mare bred by the Royal Jordanian Stud, with a pronounced jibbah, but no actual dish.

Pilarka (Palas x Pierzga), a multiple international show champion mare in the 1980s. Although she had barely any trace of a dish, no one could accuse this mare of being less than typey.

Pilarka (Palas x Pierzga), a multiple international show champion mare in the 1980s. Although she had barely any trace of a dish, no one could accuse this mare of being less than typey.

Europejczyk (El Paso x Europa), 1988 Polish National Champion and Triple Crown-winning racehorse. A very dry head with a flat forehead and slightly raised nasal bone.

Europejczyk (El Paso x Europa), 1988 Polish National Champion and Triple Crown-winning racehorse. A very dry head with a flat forehead and slightly raised nasal bone.

The great Khemosabi (Amerigo x Jurneeka) at age 30, showing the classic, slightly dished profile seen in 19th century paintings.

The great Khemosabi (Amerigo x Jurneeka) at age 30, showing the classic, slightly dished profile seen in 19th century paintings.

Marwan Al Shaqab (Gazal Al Shaqab x Little Liza Fame), World Champion and one of the architects of modern breeding. His classic, lightly dished profile is not very different from Khemosabi.

Marwan Al Shaqab (Gazal Al Shaqab x Little Liza Fame), World Champion and one of the architects of modern breeding. His classic, lightly dished profile is not very different from Khemosabi.

WH Justice (Magnum Psyche x Vona Sher-Renea), who, along with Marwan Al Shaqab, is a cornerstone of modern, show-oriented breeding. Classically beautiful in every respect, but far from extreme.

WH Justice (Magnum Psyche x Vona Sher-Renea), who, along with Marwan Al Shaqab, is a cornerstone of modern, show-oriented breeding. Classically beautiful in every respect, but far from extreme.

Essteema (Essteem x Menascha) as a yearling in 1999, when she became the first filly to win the Triple Crown (World, European, and All Nations Cup Champion). The very pronounced jibbah was unusual for her time and makes her head look extreme, but it is not technically a dish.

Essteema (Essteem x Menascha) as a yearling in 1999, when she became the first filly to win the Triple Crown (World, European, and All Nations Cup Champion). The very pronounced jibbah was unusual for her time and makes her head look extreme, but it is not technically a dish.

The extremely dished head of SHF Pearlie Mae (SHF Southern Whiz x Citona), 1996 World Champion Mare. Unlike Essteema, she has a raised nasal bone in addition to the pronounced jibbah, creating a deep dish. Unlike Essteema, she was a fluke. Neither her full siblings nor her produce had heads like this.

The extremely dished head of SHF Pearlie Mae (SHF Southern Whiz x Citona), 1996 World Champion Mare. Unlike Essteema, she has a raised nasal bone in addition to the pronounced jibbah, creating a deep dish. Unlike Essteema, she was a fluke. Neither her full siblings nor her produce had heads like this.

Rusleem (El Saleem x Rullante), an Irex descendant demonstrating how the blown-out nostrils may raise up the entire muzzle to creature the impression of a dish.

Rusleem (El Saleem x Rullante), an Irex descendant demonstrating how the blown-out nostrils may raise up the entire muzzle to creature the impression of a dish.

Hanan (Alaa El Din x Mona), foundation mare of Dr. Nagel’s famous straight Egyptian breeding program, in old age. She was a beautiful mare, but her profile was quite straight.

Hanan (Alaa El Din x Mona), foundation mare of Dr. Nagel’s famous straight Egyptian breeding program, in old age. She was a beautiful mare, but her profile was quite straight.

NK Kamar El Din (NK Hafid Jamil x Ansata Ken Ranya), linebred Hanan stallion with a perfect, typey head, but only the slightest dish.

NK Kamar El Din (NK Hafid Jamil x Ansata Ken Ranya), linebred Hanan stallion with a perfect, typey head, but only the slightest dish.

This filly of Crabbet/CMK breeding perfectly shows the hallmarks of the Arabian head from the front: the broad forehead, big and wide-set eyes, and large, expandable nostrils.

This filly of Crabbet/CMK breeding perfectly shows the hallmarks of the Arabian head from the front: the broad forehead, big and wide-set eyes, and large, expandable nostrils.

Vinca (Niel x Ojala), a straight Spanish mare not of show bloodlines, with a pronounced, but not exaggerated jibbah leading into an otherwise straight, but very refined head.

Vinca (Niel x Ojala), a straight Spanish mare not of show bloodlines, with a pronounced, but not exaggerated jibbah leading into an otherwise straight, but very refined head.

Van Gogh AM (Magnum Psyche x Ynazia HCF), a popular sire of modern show bloodlines, showing the line of the profile tilting upwards with fully blown-out nostrils.

Van Gogh AM (Magnum Psyche x Ynazia HCF), a popular sire of modern show bloodlines, showing the line of the profile tilting upwards with fully blown-out nostrils.

Ainhoa Saadeen (Perfect De La Fon x Ainhoa Sanaa), 2006 stallion of mixed, but predominantly Spanish lines. This horse won his class at the 2016 European championships, which would be hard to imagine today. But despite having no dish at all, this, too, is a perfectly acceptable Arabian head.

Ainhoa Saadeen (Perfect De La Fon x Ainhoa Sanaa), 2006 stallion of mixed, but predominantly Spanish lines. This horse won his class at the 2016 European championships, which would be hard to imagine today. But despite having no dish at all, this, too, is a perfectly acceptable Arabian head.