Reassessing the Arabian Scorecard

by Scott Benjamin

Ever since Arabian shows were first organised across Europe in earnest in the 1970s, the Arabian scorecard has been an essential tool in the assessment of the breed in the showring. The earliest attempts to assess breeding horses included a scorecard devised in Sweden, which used a scale of 1 to 5 with half points. This rudimentary scorecard later evolved into a ten-point scale, finally coalescing into the twenty-point scale that has become the global standard today. The adoption by the European Commission of Arabian Horse Organizations (ECAHO) of this version of the Arabian scorecard as the standard by which all breeding horses should be assessed at shows sanctioned by the governing body established the scoring framework as an essential hallmark of the international showring. This same scorecard has since been adopted, and in some cases modified, on nearly every continent where Arabian horses are bred and shown.

As a tool of assessment, the scorecard has a multitude of attributes:

- Principally, the scorecard allows a judge/assessor the opportunity to score a horse in relation to the breed standard, the millennia-old breed ideal which is the classic war horse of the desert;

- Ideally, the scorecard also increases objectivity of assessment, requiring the judge/assessor to score each horse according to a clearly prescribed and well-defined standard across a series of primary characteristics, which are then assigned a corollary score on a scale ranging from poor (10) to ideal (20);

- Conversely, use of the scorecard reduces subjectivity, which minimises personal opinion, feelings and bias;

- The scorecard is an uncomplicated, easily comprehensible, time-efficient numerical assessment tool, which can be readily repeated across large numbers of horses at a singleevent;

- This same numerical assessment tool can be easily replicated anywhere else in the world to hold all horses assessed accountable to a global standard, which enables the reliable identification of quality bloodstock without direct comparison;

- When utilized properly, the scorecard can serve as an accurate assessment of the phenotypic merit of individual horses, which can in turn be a valuable breeding and selection tool.

It is important to understand that the Arabian scorecard that is utilized in the international showring does not result in a proper breeding evaluation. It is not possible, given the time and spatial constraints in the modern showring of two to three minutes of assessment per exhibit in the company of as many ten other people surrounding the same horse, to properly evaluate and score breeding stock. Detailed breeding assessments, which are imperative for the progress and preservation of the breed, require more time, more detail and more reflection, and by all means should be undertaken with a group of qualified professionals who are free to discuss and debate during the process.

As the global pool of judges has evolved and expanded, so too have scores awarded at shows utilizing the Arabian scorecard.

As with anything in life, a tool is only as good as the artisan who wields it. The Arabian scorecard is a tool wielded by the judge, ideally a well-trained, highly-qualified professional with years of experience, knowledge and expertise, one who has great clarity and awareness of the ancient breed ideal. As judges, we bear an immense responsibility each time we step into the ring. In descending order of magnitude, these are the pillars of the system we are bound to uphold:

- The integrity of the Arabian breed, both the preservation and advancement;

- Our own personal character and integrity;

- The breeders responsible for envisioning and creating the horses on exhibit;

- The owners who have given of their time and resources to bring their horses for assessment;

- The professionals who present, prepare and care for the horses;

- The show organisers who create the opportunity for breed promotion and a greater sense of community;

- The general public who we must engage, educate and entertain

I discovered the rewards of judging early in life, as a member of both equine and livestock collegiate judging teams while earning my undergraduate degree at Michigan State University in the late 1980s. It was here I was taught the fundamentals of form to function, proper breed type for a multitude of species and the tools to not only methodically and thoroughly evaluate individual animals, but to communicate those assessments and the conclusions drawn both through written critique and oral discourse. I have had the supreme privilege of assessing tens of thousands of animals, mostly Arabian horses, over the course of my life, on every inhabited continent. In so doing, I have also enjoyed the company of hundreds of fellow professionals from whom I have fortified my knowledge and proficiency, and with whom I have expanded my perspective and experience.

The vast majority of fellow judges encountered during the earliest decades of my judging career were breeders or trained equine professionals, serious, dedicated and passionate men and women who had devoted decades of their lives to promoting and advancing the Arabian breed. They understood clearly, without equivocation, their responsibility as a judge each time they were handed scoring sheets and walked into the ring, unafraid to assign scores that accurately reflected the attributes possessed by each horse that was presented. They also recognised that these same scores had practical application in comparative championships, and that higher scoring horses should be rewarded with a higher ranking in the final, with the occasional realignment when the final scores differed by just tenths of a point. There was logic, integrity and resolution in their behaviour and decision-making, with respect and appreciation reciprocated from breeders, owners, trainers and show organisers in return.

Somewhere along the way, this older generation of experienced practical horsepersons has been replaced by a larger number of equine hobbyists and enthusiasts, those who view the Arabian horse as more of a lifestyle or a business, rather than as a serious pursuit of breed preservation and responsible stewardship. I believe that there is a need for both sorts of judges, in equal numbers, in our modern industry. This will make our judging pool more representative, both in national judging lists worldwide, and also panels adjudicating international events and national championship shows, where the assessment of breeding stock is most critical.

Somewhere along the way, this older generation of experienced horsepersons has been replaced by a larger number of equine hobbyists and enthusiasts, those who view the Arabian horse as more of a lifestyle or a business, rather than as a serious pursuit of breed preservation...

As the global pool of judges has evolved and expanded, so too have scores awarded at shows utilising the Arabian scorecard. World, European and All Nations Cup Championships were routinely awarded to horses scoring in the high 80s, calculated as a percentage, for several years, with the assignment of a perfect score of 20 a rare reward for an extraordinary performance or an exceptional attribute. Inevitably, as the quality of presentation and preparation improved, scores began to rise into the nineties — now the standard to beat for a place on the podium in elite level competition. Show attendance also grew in popularity from the 1980s onward, the result of which was more high-quality horses entered and another another round of awarding higher scores.

This upward drift has occurred not only at the elite level but seemingly at every level of shows, even in the remotest regions of the world, in what appears to be an attempt to legitimise the importance of these events and the quality of exhibits presented to a status equal to that of the breed elite. A total score equalling 92% or above would have been celebrated by experienced breeders, owners and professionals, and reflective of the uppermost echelon of the breed at the turn of the millennium. This seems to be the minimum score now required to satisfy owners and trainers at any show and to be worthy of a top five class placing, regardless of the depth and breadth of quality present at the event.

For those with practical breeding experience, especially within large herds of horses, this unrealistic expectation that the majority of horses presented at every level of show must achieve 92%, even 90%, and above is untenable. Practised breeders understand that on average, in any given foal crop, only 5-10% of foals born will qualify as elite, representing the very best of the breed. The next 20-25% of that same foal crop, will, on average, be considered premium, reflecting high quality breeding and show stock with a greater proportion of exemplary attributes than the breed average. The largest portion of any foal crop, again on average, will be comprised of good quality foals at 25-35% of the total, those with attributes slightly above or equivalent to the breed standard, but unlikely to be elite level performers either under saddle or in-hand, but still capable of contributing to the next generation with a net positive effect. Also readily apparent to seasoned breeders is the fact that a portion of any foal crop, on average in the range of 15-30%, will be sub-standard, possessing a combination of attributes that are collectively ranked below the breed average. These horses are not only unlikely to ever be shown and are those most often culled by wise breeders for uses other than breeding.

We also know that globally, the percentage of Arabian horses shown compared to number of horses registered each year in any given country is between 10% and 20%. The vast majority of Arabian horses bred everywhere in the world are NOT shown, which would plausibly include that lowest percentile of substandard foals that are an unavoidable consequence of breeding and selection.

Logically, not every horse considered elite, premium and quality will be shown at every event, nor will they be shown every year. The vast majority of horses will not be shown past the age of 10, with numbers in each age group dwindling from one year of age onwards for breeding stock. Almost everywhere in the world those horses considered as substandard will remain unshown. At any given Arabian show, the percentage of horses shown in comparison to the total population of horses in the country/region is less than 1%.

With this understanding of breed composition and rates of exhibition, we can make the following suppositions about a fictitious mid-level horse show anywhere in the world at which 100 horses are presented.

- Horses considered substandard would be unable to score 70% if assessed using the current scorecard. One would therefore expect nearly 100% of the horses assessed to achieve total scores higher than 70%;

- Most horses considered good quality would unlikely be chosen for show preparation and presentation if horses of higher levels are also present in the herd at the same farm/training centre. Horses considered qualitywould score between 70% and 85%, the largest range for the largest proportion of the breed population. Therefore, scores in this range would be less likely at the average show, but not unrealistic;

- Horses categorised as premium are more likely to be selected for show preparation, especially under the age of three. These horses can vary greatly in maturity and growth as youngsters, but the average scores for horses in this group should total, on average, between 85% at the lower threshold and 90-91% on the upper limit. Breeders often find that horses assessed as premium may mature into elite level horses, with the occasional individual proving to be good quality once reassessed as an adult;

- The exclusive categorisation of elite is reserved for the smallest percentage of the population, which in reality is closer to the upper 5% rather than 10%. When possible, taking into consideration all the factors such as access to shows, physiological readiness, soundness, financial constraints, etc., the vast majority of these horses will be shown at some point in their lives. Horses classified as eliteare typically shown more selectively, as those that achieve the highest accolades rarely return to challenge a title already accrued. Horses universally recognised as elite should consistently score 91% and above should they be conditioned and perform close to peak.

These categories equate to roughly the following distribution of horses among a population of 100 shown at any ECAHO show rated B or below:

- Good Quality– 15% (15 entries) awarded scores below 85%

- Premium– 70% (70 entries) awarded scores ranging from 85% to 91%

- Elite– 15% (15 entries) awarded scores 92% and above

Most often, horses selected for shows that are classified as premium tend to be closer to elite than to good quality, which may net scores that are closer to the high end of the range.

Before we go any further, we should have a clear understanding of what scores must be awarded in order to achieve a cumulative score of 92% using the Arabian scorecard. Minimally, a horse will need to score, on average from all of the judges, 19s in the four categories in which such scores are typically assigned – TYPE, HEAD & NECK, BODY & TOPLINE as well as MOVEMENT, and a 16 for FEET & LEGS, which has become the acceptable standard for “good” legs and often the upper limit that the majority of judges feel comfortable awarding. That equates to four scores of “excellent,” – the word ascribed to a score of 19, and one score of “above average,” which is ascribed to the score of 16. Any horse that receives four scores of “excellent,” and the highest “acceptable” standard for the fifth score should indeed be considered an elite horse, one of the very best of the breed. Any horse that scores higher in any of the four premier categories with a score of 19.5, still considered “excellent,” or a 20, which should only be awarded when the “ideal” is displayed. These horses are the standard setters of the era…icons for decades to come.

How then have owners, trainers, show organisers, and in some cases, breeders, become dissatisfied when the vast majority of scores awarded at any show outside of A-level and title shows, are less than 92%, especially when one knows that a score of 19 for BODY & TOPLINE is rare? The scores greater than 92% arereserved for the best, which comprise the smallest percentage of horses at any show at every level. In some outrageous instances, exhibitors have demanded scores closer to 94% for the majority of horses shown, which equates to at least one perfect 20 and at least two 19.5s. The improbable score of ninety-five has become the new “mark of excellence,” which can only be achieved with a minimum of three perfect 20s in at least three categories, a BODY & TOPLINE score of no less than 19, and no FEET & LEGS scores below 16 – across the average of the panel of three-plus judges. Nearly five decades of experience as a judge, breeder and a university-trained equine professional has taught me that such scores are not only rare, but they are also to be assigned only when true excellence is presented to us.

A score of 92% equates to excellent – any horse that receives this score or higher in the showring should be described, without hesitation, as excellent by the vast majority of honourable and competent professionals. If the words good or very good are used more frequently to describe the horse in question, those descriptions equate to scores lower than 92%, which are still respectable and worthy of recognition. It is the breed standard that defines the upper limit of what is possible. Every pragmatic horseperson knows that perfection is unattainable. Even excellence is difficult to achieve, and even harder to maintain, much less exceed, over time. We should all be seeking a world in which 92% again becomes the global gold standard.

The questions remain:

- How do we correct the upward drift of higher scores?

- How can we modify the current Arabian scorecard to make it easier for capable judges to assign an accurate score for each category of assessment?

- How can we realign the total scores awarded at every level of show to more precisely reflect the international breed standard?

A practical answer to all the above questions became evident after attending both European-based ECAHO-sanctioned A shows this past summer: the Mediterranean & Arab Countries Championships in Menton in late June and the Prague Intercup some eight weeks later in mid-August. Both shows utilized the ECAHO-standard scorecard which evaluates horses in the five classic categories: 1) TYPE; 2) HEAD & NECK; 3) BODY & TOPLINE; 4) FEET & LEGS; and 5) MOVEMENT. The decision, however, to split the category of HEAD & NECK into separate scores of 20 points for HEAD and for NECK each, and to then total and average those scores into a single categorical score, was a revelation. Several horses present in Prague had also participated in Menton. It was illuminating to discover the consistently lower, and more representative, scores for HEAD & NECK assigned to these same individuals, many of them characterised as excellent, at the second event. The the overall scores achieved in Prague for these same horses were slightly lower and more realistic, yet still comfortably in the zone of excellence above 92%, which was merited for the majority of exhibits who attended both events.

Would these enhanced scorecards, requiring more scores to be assigned, remain practical and feasible given the time constraints of individual assessment in the modern showring?

Having had the opportunity to use scorecards with spilt categories in the past, especially at the innovative International Arabian Horse Days in Ströhen, I understood the practical application and merit of subdividing the major categories of assessment into the most essential components, that when recombined, created a more truly representative whole. I had not, however, seen this same innovation applied in elite level competition, nor the comparison made of the same elite-level horses across both systems in a single season. If the category of HEAD & NECK could be separately and more accurately scored with qualified judges at the highest level of competition, could we not subdivide the other major categories to achieve corollary success? Could we, and should we, subdivide the subcategories of HEAD & NECK even further, so that the scores assigned to components can more accurately reflect the phenotype being assessed? Would these enhanced scorecards, requiring more scores to be assigned, remain practical and feasible given the time constraints of individual assessment in the modern showring?

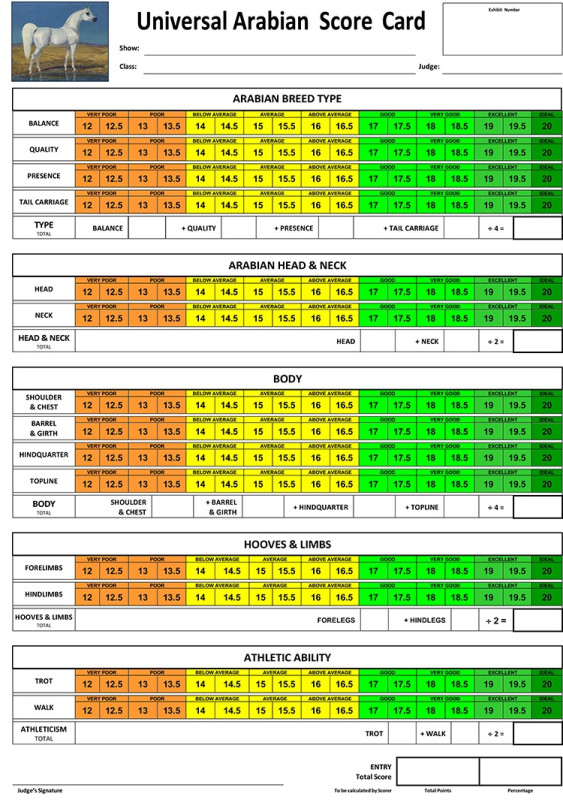

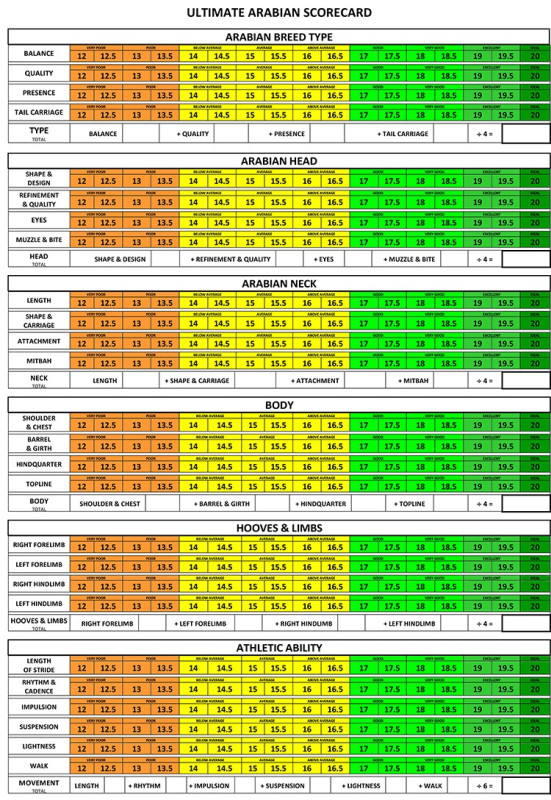

These theoretical questions have since inspired the creation of two enhanced scorecards: the more concise Universal Arabian Scorecard and the more exhaustive Ultimate Arabian Scorecard. In a perfect world, I would love to hold every exhibit at all A-level shows and above to this more demanding standard, as it is these horses that are most often acclaimed as the best of the present generation, and around whom far-reaching breeding decisions are routinely made. I do, however, understand that assigning more than five times as many scores – 27 instead of 5 – in the span of one to two minutes in a showring is impractical. My hope, nonetheless, is that a scorecard such as this could become an essential teaching and training tool for judges worldwide, providing greater enlightenment and a more comprehensive understanding of the components that equate to a total categorical score. When one is forced to break down each major category into subcomponents and assign scores separately and more accurately, it is apparent that a perfect score of 20 is nearly impossible to achieve, and that even a 19.5 requires a consensus of excellence across the board.

The more applicable Universal Arabian Scorecard will make its debut at the Australasian Arabian International Championships in February of 2024, where we plan to ask the judges of the best breeding stock in Australia and New Zealand to use this enhanced tool. I expect fewer perfect scores of 20 for TYPE, HEAD & NECK and MOVEMENT, as is reflective of exemplary breeding stock worldwide, and more accurate scores, in many cases even higher, in the categories of BODY & TOPLINE and FEET & LEGS. The ultimate aim will be to test the efficacy of this modified scorecard in real time with internationally accredited judges who understand exactly what is at stake.

My hope is that breeders, judges, owners and professionals all around the world, and chiefly our beloved Arabian horse, will benefit as a result. Stay tuned for the results – there is so much more to come…