Remembering Chaldoran Mir Yazd,

by Emma Maxwell

I wrote this story the end of last year, and then sighed with regret at the possibility of posting a story set in a nation whose government seemed to be so keen on exacerbating the woes of the world. But the Arabian horse community is genuinely worldwide. We all share the same passion, and if I excluded writing about horses from countries of whose governments I did not approve – well – perhaps I would hardly have anything to write about at all!

Back in 2005 I was invited by Sharzad Amir Aslani to judge some of the first Arabian horse shows in Iran, kickstarting an excellent friendship with Shery and Hilly Benjamin, with whom whom I had several adventures in their homeland. I accepted the invite with enthusiasm, unlike so many countries, Iran was one where I did not really know what to expect. Considered by the West as a pariah state since the 1979 revolution, (which reputation it appears to be doing its best to maintain), this relentlessly negative narrative contrasted strongly with every other account of the country I had ever read. Those accounts were also right, Iran is a fantastically beautiful place with an abundant history of previous civilizations and many well-informed, enthusiastic and tremendously hospitable people. And, like every other country with Arabian horses I have visited, an instant group of new and wonderful friends with stories to tell.

I stayed on after a show in the central city of Yazd, which was a noisy and excitable event in a basketball arena. To show me around, Agha Zia Vakil al Sadat, one of the local breeders and a successful businessman in the area had proposed a desert ride of 130 kilometres over two days, for which he would lend me a horse. Several other local breeders would be joining, along with Shery and Hilly, heading northeast towards Afghanistan, spending one night at a Silk Road caravanserai and ending at the Zoroastrian Pir-e-Sabz Fire Temple, known as Chak Chak. Forget Rolexes – not that I have ever had one – this was by far the best post-judging gift ever. I was forewarned about it before arriving, and so had brought a decent sheepskin numnah and comfortable girth to leave as a gift for the horse I was to ride.

Agha Zia lent me a horse named Chaldoran Mir Yazd, a dapple grey five-year-old, a son of his best stallion Barfin, who was the most successful sire bred in Iran at the time. Barfin was by the Nagel-bred Mubarak, a Salaa El Dine son, who had been something of an “Aswan” in Iran, breeding Egyptian type on the Iranian stock without necessarily losing their toughness. His dam was of all Iranian lines. Chaldoran was a long-legged, long-necked horse who was easy to get to like.

“This was by far the best post-judging gift ever – a 130-kilometre ride on a racing Arabian in Iran, and a night at a Silk Road caravanserai.”

It took us most of the morning to get started, tacking up fourteen horses in something that fitted comfortably and was not going to fall apart on a two-day mission was a quest in itself. Agha Zia’s wife Parisa, a dentist by trade, was riding too, she had learnt to ride recently because she was annoyed with her husband for disappearing on these weekend long rides with his friends. She rode a magnificent but slightly battered black Iranian stallion called Tuhotmos, with a ladylike handbag slung over one shoulder.

Half a mile out from the yard we arrived at the main highway which we had to cross. We flagged down the trucks on the highway, skittered across the tarmac and rode out into the wilderness. I was not really fit enough for a ride of such a distance but I was very delighted with my horse, who had a smooth long stride and was obliging whether in front of a group or behind. I knew most of the young stallions in Iran raced so I asked why he was not on the track, because five years old seemed the ideal racing age. I was completely horrified when the answer was: “He tweaked a tendon a few months ago.” I did not dare ask what part of his convalescence was being lent to the foreign judge to ride 130 kilometres in the desert, but focused on avoiding rocks, ruts and deep sand, while trying not to accelerate, brake or turn corners too fast. You will be glad to hear he remained sound!

As we had set off late, we arrived at the Kharanaq caravanserai after sunset when the heat of the day had already turned into the sharp cold of a desert night. The horses were tied to the outside wall, swaddled in homemade lambswool and carpets, and given a nosebag of food. One of the families riding had prepared a cauldron of lamb stew for us, but as this bubbled temptingly on the fire in front of us, he announced that he had forgotten all the plates and cutlery and drove the 60 kilometres back to town to fetch them while we slowly starved. Dinner was finally served after midnight and I hobbled to my bed in one of the little arched rooms set into the outer wall of the courtyard. Lovingly restored by the Iranian antiquities board, and a UNESCO World Heritage site, every stone was intact. Including the cobbled floor of my cell, which left me with a nice pattern of imprints through my sleeping bag as the night passed.

The next morning I swallowed a handful of painkillers and went to find my horse. All the stallions had finished their morning nosebag and looked well rested. The liveliest one, an attractive white son of Mubarak, named Benazir, was already pawing the ground in enthusiasm. Benazir was a horse whose antics I had disapproved of the day before. As the main group walked, trotted or cantered slowly onwards, Benazir would gallop off into the distance in front of us. Hang about for a bit. And then gallop back! He clearly had a mouth like iron and regularly swapped riders to give them some relief, but I could not believe how many extra miles he was doing, and at what speed! Whenever I asked, my fellow riders would smile fondly and say, “Ahh, it’s Benazir.” I did not understand this answer, so I persisted and finally got the whole tale which turned out to be as improbable as “National Velvet” (but without Elizabeth Taylor).

“Benazir was a horse whose antics I had disapproved of the day before.”

Benazir was famous across Iran for once entering every race on the race card – all six of them – and winning all of them. There was more to the story.

Emma Maxwell was in Iran for a judging assignment…it quickly turned into a spectacular adventure.

The lovely stallion Chaldoran Mir Yazd (the grey on the right), winning his race in Dezful. He was Emma Maxwell’s mount for a 130 km ride in Iran.

Chaldoran Mir Yazd.

The Nagel-bred stallion Mubarak, a Salaa El Dine son, who had been something of an “Aswan” in Iran. His dam was of all Iranian lines.

After the show, local Arabian breeder and business man, Agha Zia Vakil al Sadat, invited Emma and friends on a two-day 130km ride. Agha also supplied her mount, Chaldoran Mir Yazd (by Barfin who in turn was sired by Mubarek).

Iran, as you may recall, is next door to Afghanistan and its famous poppy. Benazir was previously owned by an old man, who in the tradition of the region smoked opium in his old age, as it lowers the blood pressure and whiles away the long evenings. When the old man died, his family noticed that after a couple of days his horse had started to show opioid withdrawal symptoms and realized he had been keeping his owner company in more ways than one. The six races seemed more plausible now – but still, what a fabulously tough horse to have lasted so long with all his pain receptors turned off. I started to smile fondly and go “Ah, Benazir” too!

The second day’s ride was reputedly much shorter than the first, and our destination was regularly promised to be “Just around the corner of the next mountain.” Several mountains later, I was definitely flagging, but the end finally came into view that afternoon. The 1400-year-old pre-Islamic shrine is a tiny grotto halfway up the side of a mountain. It has been built around a trickle of water that emerges constantly from the rocks and is usually known after the noise of the dripping water: Chak Chak. The tiny temple hosts an eternal flame that has been kept burning by Zoroastrian priests since the end of the Sasanian Empire. After a night on the cobbles and two days in the saddle, climbing the 366 steps up to it was daunting. For years I have been telling people there were a thousand steps, which is what it felt like – I only just now looked up the actual number, for reasons of journalistic integrity! Whatever the number, I think did the last 100 or so on hands and knees.

It was a strikingly affecting place, Zoroastrianism was the first monotheistic religion and this tiny shrine, so old and so unfamiliar, had an otherworldly atmosphere. While Iran is an Islamic Republic, it was illuminating to see that it still maintains these pre-Islamic shrines and allows the remaining Zoroastrians to maintain them.

“I gave a demonstration on how to show horses out in the wasteland by the stables, where I made a classic error that I have never made again…”

As the sun started to set, our transport home arrived. We went home in cars. The 14 horses shared two open-topped, flat-bed, metal-floored trucks. The trucks were backed up to a mound of earth, a scattering of sand was put on the floor and then each stallion neatly hopped in, was tied up to the side railing, a rope was passed down beside him and tied to the railing on the other side as a partition and the next horse led in. All of them stood peacefully for the drive home wearing their nosebags.

Two years later I returned to Iran to judge again in another area of the country, Khuzestan in the southwest just over the border from Iraq. Our host on this occasion decided that rather than lend the judge a horse after the event, he might try and influence her decisions by lending her a nice horse to ride the day before the show – a rather fancy bright chestnut stallion in race training, who was also entered for the show. (This was pre-ECAHO, by the way, before you start sending in your complaints!). Once I had accepted this offer, every horse owner in the region seemed to materialise out of nowhere to assess the judges’ riding skills. So my mount was now getting quite antsy amid a jostling crowd. Bear in mind the need for a headscarf to be demurely in place at all times in public in Iran, and I realized I was going to have to mount single-handed while holding my headscarf on with the other hand. The man holding the horse helpfully assisted by pulling him firmly downwards in the mouth every time my foot was in the stirrup causing the horse to rear. Eventually, I convinced the handler to leave, swung onto the horse and kicked off at gallop for a circuit of the field, predicting that tomorrow’s exhibitors were unlikely to respect a judge who could only manage a polite trot.

After the show, my location was discovered by breakfast time next morning and a long queue formed for me to explain every single placing in great detail. When judging small shows with inexperienced owners, actually its best to get on the microphone at the end of the class, but if not…I find it is very helpful to try to memorize each horse in three short sentences, so I can articulate my reasons for each placing in case of any post-event inquisitions! Just remember to translate the sentences before opening your mouth. “Shiny bay with dapples. Yellow plastic bridle. Hideous, extremely fat and cobby with coffin head and tiny hocks. LAST!” becomes. “The dark bay colt? With the yellow bridle? Beautiful coat, so nicely presented. And so big! Yes, Definitely, the biggest horse in the class. Um. Perhaps this was the problem. He would look more Arabian carrying a bit less weight next time.” And so on.

Emma and Chaldoran follow Fallat and Gavidan.

Agha Zia’s wife, Parisa, recently learned to ride, and joined us for the adventure.

Lunchtime in Yazd.

The 4,500 year old abandoned mud village just outside the Caravansary… they were originally built at same time but the caravanserai was rebuilt by the Qajars.

Kharanagh Caravansary.

On the way back to Tehran, we went to a race meeting on the outskirts of a city named Dezful near the Euphrates. This was not a race meeting for the faint-hearted. We arrived long before the races started but already the loudspeakers were pumping out music and it seemed every young man in town was arriving on a motorbike. Iran, of course, does not have nightclubs, so it seemed that a day at the races was going to have to do. Lots of women came too, but they appeared to have their own specified pickup trucks to stand in as designated Ladies Areas. The stables out the back were a mixture of temporary boxes set up by the richer owners, and ropes tied to electricity poles, or a ground tether for the rest. Local horses arrived on the back of a pickup. Every horse wore a plastic wastepaper basket on its face to stop them from eating sand, Iran is a country with brilliant skills of repurposing.

“…he at least looked like a show horse, but he absolutely refused to take any instruction, not even the tiniest step backward.”

I gave a demonstration on how to show horses out in the wasteland by the stables, where I made a classic error I have never made again. However quiet and dull the horse you are handed to demonstrate with is, never ever ask for a livelier one. A ripple passed through the crowd as my request was translated. The colt I had was taken off my hands and 15 minutes later the new model arrived. With a man hanging on each side of his bridle, Damavand, who was named after the tallest volcano in Asia, a snow-capped peak in the north of Iran. A tall, imperious horse (also a son of Mubarak, and one with a clear look of Morafic) he at least looked like a show horse, but he absolutely refused to take any instruction, not even the tiniest step backwards…something I was trying to teach the crowd. My audience melted away.

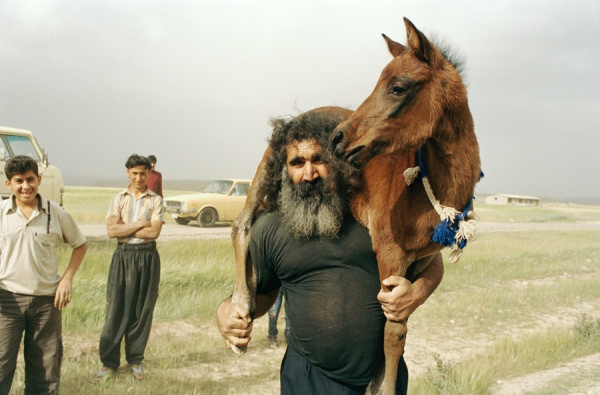

Seminar ignominiously over, we set off to watch the races. What a race meeting! The contestants wove their way between the motorbikes to get to the starting gates where an enormous bearded man called Pahlevan shoved the reluctant ones in singlehanded. Before race five, a mare with foal at foot turned up. Pahlevan hoisted the foal onto his shoulders where it remained, totally relaxed for the entire race while its mother competed. She was second. The foal was returned unharmed and hung around while his mother gave pony rides. Then the final race lined up. This was the last meeting of the season and this race was the big championship of the region. There was something I liked about the tall grey horse on the inside rail who effortlessly won the event, but I did not immediately recognize him. It was Chaldoran – whose long ride with me two years before had fortunately not caused his tendon further damage.

“Versatile Arabians, who let anyone ride them across a desert, have more interesting lives than show horses, and can capture imaginations just as effectively if not more.”

In 2022 I was thrilled to see that Chaldoran, was awarded the WAHO Trophy by the Iranian Breeders Association. His write-up says:

“Chaldoran Mir Yazd began a very successful racing career at three-years old. He never lost a single race and after retiring from the racetrack at eight years of age, he continued as an endurance horse. Chaldoran was also used at stud and his offspring followed the same path of their sire. At 22, he still has the same spirit of his youth, with outstanding sound legs.

“His dam Azizeh, comes from a well-known family belonging to the Nesman strain bred by Majid Bakhtiar, from the Bakhtiari tribe.

“Chaldoran was chosen as he represents the best of Iranian bloodlines, a blend of Egyptian blood with our Asil mares, with correct conformation, strong body and a wonderful disposition. And it is these traits that allow versatility in performance disciplines.”

I realize when I think about some of the great Arabian horses I have met in faraway places, that we have become as unhealthily obsessed by celebrities in horse culture. Sometimes there can be little more to say about the celebrity except they are jolly pretty. Their prettiness can imprison them in the industrial requirements of Instagram and artificial breeding: a life of neck-sweats, photoshoots and endless visits to the repro clinic. Versatile Arabians, who let anyone ride them across a desert, have more interesting lives, and can capture imaginations just as effectively if not more.

Photos by Sharzad Amir Aslani, Jude Edginton, and Emma Maxwell.

One evening on the way back to Tehran we stopped at a race meet, complete with pony rides, on the racehorses no less!

An enormous bearded man called Pahlevan shoved the reluctant ones into the starting gate singlehanded.

Before race five, a mare with foal at foot turned up. Pahlevan hoisted the foal onto his shoulders where it remained, totally relaxed for the entire race while its mother competed.

Here is Chaldoran Mir Yazd, happy at home with his family.